Ultrasound Reading of Fluid Between Baby and Placenta More Than 3.5 Cm

| Placenta | |

|---|---|

Placenta | |

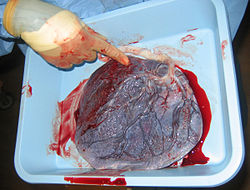

Man placenta from just after birth with the umbilical string in place | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | decidua basalis, chorion frondosum |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Placento |

| MeSH | D010920 |

| TE | E5.11.three.1.1.0.5 |

| Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

The placenta is a temporary fetal organ that begins developing from the blastocyst shortly after implantation. It plays critical roles in facilitating nutrient, gas and waste product exchange betwixt the physically separate maternal and fetal circulations, and is an important endocrine organ producing hormones that regulate both maternal and fetal physiology during pregnancy. The placenta connects to the fetus via the umbilical cord, and on the contrary aspect to the maternal uterus in a species dependent manner. In humans, a thin layer of maternal decidual (endometrial) tissue comes away with the placenta when information technology is expelled from the uterus following birth (sometimes incorrectly referred to as the 'maternal part' of the placenta). Placentas are a defining characteristic of placental mammals, but are too plant in marsupials and some non-mammals with varying levels of development.[1]

Mammal placentas probably first evolved about 150 million to 200 one thousand thousand years ago. The protein syncytin, found in the outer barrier of the placenta (the syncytiotrophoblast) betwixt mother and fetus, has a certain RNA signature in its genome that has led to the hypothesis that it originated from an ancient retrovirus: essentially a "good" virus that helped pave the transition from egg-laying to live-birth.[ii] [3] [iv]

The word placenta comes from the Latin word for a blazon of cake, from Greek πλακόεντα/πλακοῦντα plakóenta/plakoúnta, accusative of πλακόεις/πλακούς plakóeis/plakoús, "flat, slab-like",[five] [half-dozen] with reference to its round, flat appearance in humans. The classical plural is placentae, but the form placentas is more common in modern English.

Phylogenetic diversity [edit]

Although all mammalian placentae have the same functions, there are important differences in construction and function in different groups of mammals. For example, homo, bovine, equine and canine placentae are very different at both the gross and the microscopic levels. Placentae of these species too differ in their ability to provide maternal immunoglobulins to the fetus.[7]

Structure [edit]

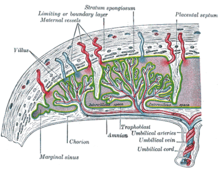

Placental mammals, such as humans, accept a chorioallantoic placenta that forms from the chorion and allantois. In humans, the placenta averages 22 cm (9 inch) in length and 2–2.5 cm (0.viii–1 inch) in thickness, with the center being the thickest, and the edges existence the thinnest. Information technology typically weighs approximately 500 grams (only over 1 lb). It has a dark ruddy-blue or crimson color. Information technology connects to the fetus by an umbilical cord of approximately 55–60 cm (22–24 inch) in length, which contains two umbilical arteries and ane umbilical vein.[viii] The umbilical cord inserts into the chorionic plate (has an eccentric attachment). Vessels branch out over the surface of the placenta and further dissever to form a network covered past a thin layer of cells. This results in the formation of villous tree structures. On the maternal side, these villous tree structures are grouped into lobules called cotyledons. In humans, the placenta usually has a disc shape, but size varies vastly between unlike mammalian species.[9]

The placenta occasionally takes a form in which it comprises several distinct parts connected by blood vessels.[10] The parts, called lobes, may number two, three, four, or more. Such placentas are described as bilobed/bilobular/bipartite, trilobed/trilobular/tripartite, and so on. If there is a clearly discernible master lobe and auxiliary lobe, the latter is called a succenturiate placenta. Sometimes the blood vessels connecting the lobes arrive the style of fetal presentation during labor, which is called vasa previa.

Factor and poly peptide expression [edit]

Near 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and lxx% of these genes are expressed in the normal mature placenta.[11] [12] Some 350 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the placenta and fewer than 100 genes are highly placenta specific. The corresponding specific proteins are mainly expressed in trophoblasts and have functions related to female person pregnancy. Examples of proteins with elevated expression in placenta compared to other organs and tissues are PEG10 and the cancer testis antigen PAGE4 and expressed in cytotrophoblasts, CSH1 and KISS1 expressed in syncytiotrophoblasts, and PAPPA2 and PRG2 expressed in extravillous trophoblasts.

Physiology [edit]

Development [edit]

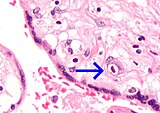

The placenta begins to develop upon implantation of the blastocyst into the maternal endometrium. The outer layer of the blastocyst becomes the trophoblast, which forms the outer layer of the placenta. This outer layer is divided into 2 further layers: the underlying cytotrophoblast layer and the overlying syncytiotrophoblast layer. The syncytiotrophoblast is a multinucleated continuous cell layer that covers the surface of the placenta. It forms as a upshot of differentiation and fusion of the underlying cytotrophoblast cells, a process that continues throughout placental development. The syncytiotrophoblast (otherwise known every bit syncytium), thereby contributes to the barrier role of the placenta.

The placenta grows throughout pregnancy. Development of the maternal blood supply to the placenta is complete by the end of the offset trimester of pregnancy calendar week fourteen (DM).

Placental circulation [edit]

Maternal blood fills the intervillous space, nutrients, h2o, and gases are actively and passively exchanged, and then deoxygenated blood is displaced past the next maternal pulse.

Maternal placental circulation [edit]

In training for implantation of the blastocyst, the endometrium undergoes decidualization. Spiral arteries in the decidua are remodeled and so that they go less convoluted and their bore is increased. The increased diameter and straighter menstruum path both human action to increase maternal claret flow to the placenta. There is relatively high force per unit area every bit the maternal claret fills intervillous space through these spiral arteries which bathe the fetal villi in blood, assuasive an exchange of gases to have place. In humans and other hemochorial placentals, the maternal blood comes into directly contact with the fetal chorion, though no fluid is exchanged. As the pressure decreases betwixt pulses, the deoxygenated blood flows dorsum through the endometrial veins.

Maternal claret period is approximately 600–700 ml/min at term.

This begins at solar day 5 - day 12[13]

Fetoplacental apportionment [edit]

Deoxygenated fetal blood passes through umbilical arteries to the placenta. At the junction of umbilical cord and placenta, the umbilical arteries co-operative radially to form chorionic arteries. Chorionic arteries, in turn, branch into cotyledon arteries. In the villi, these vessels somewhen branch to form an extensive arterio-capillary-venous arrangement, bringing the fetal blood extremely shut to the maternal claret; just no intermingling of fetal and maternal blood occurs ("placental bulwark").[xiv]

Endothelin and prostanoids cause vasoconstriction in placental arteries, while nitric oxide causes vasodilation.[15] On the other hand, in that location is no neural vascular regulation, and catecholamines accept only little effect.[15]

The fetoplacental circulation is vulnerable to persistent hypoxia or intermittent hypoxia and reoxygenation, which can lead to generation of excessive free radicals. This may contribute to pre-eclampsia and other pregnancy complications.[16] It is proposed that melatonin plays a role as an antioxidant in the placenta.[xvi]

This begins at solar day 17 - day 22 [17]

Nascence [edit]

Placental expulsion begins as a physiological separation from the wall of the uterus. The menstruation from only after the child is built-in until simply afterwards the placenta is expelled is called the "third stage of labor". The placenta is usually expelled inside xv–thirty minutes of birth.

Placental expulsion tin be managed actively, for example by giving oxytocin via intramuscular injection followed by cord traction to assist in delivering the placenta. Alternatively, it can be managed expectantly, assuasive the placenta to exist expelled without medical assistance. Blood loss and the risk of postpartum bleeding may be reduced in women offered agile management of the third stage of labour, all the same there may exist adverse furnishings and more enquiry is necessary.[18]

The habit is to cut the cord immediately after nativity, but information technology is theorised that at that place is no medical reason to do this; on the contrary, it is theorised that not cut the string helps the baby in its adaptation to extrauterine life, specially in preterm infants.[xix]

Microbiome [edit]

The placenta is traditionally thought to be sterile, but recent research suggests that a resident, non-pathogenic, and diverse population of microorganisms may be present in healthy tissue. However, whether these microbes be or are clinically important is highly controversial and is the subject of active inquiry.[20] [21] [22] [23]

Functions [edit]

Nutrition and gas exchange [edit]

Maternal side of a placenta shortly subsequently birth.

The placenta intermediates the transfer of nutrients between female parent and fetus. The perfusion of the intervillous spaces of the placenta with maternal blood allows the transfer of nutrients and oxygen from the mother to the fetus and the transfer of waste matter products and carbon dioxide back from the fetus to the maternal blood. Nutrient transfer to the fetus tin can occur via both agile and passive transport.[24] Placental nutrient metabolism was found to play a fundamental function in limiting the transfer of some nutrients.[25] Adverse pregnancy situations, such as those involving maternal diabetes or obesity, tin increase or decrease levels of food transporters in the placenta potentially resulting in overgrowth or restricted growth of the fetus.[26]

Animated schematic of the hearts and circulatory systems of a fetus and its mother – red and bluish represent oxygenated and deoxygenated blood, respectively (animation)

Excretion [edit]

Waste matter products excreted from the fetus such as urea, uric acrid, and creatinine are transferred to the maternal blood by diffusion across the placenta.

Immunity [edit]

The placenta functions equally a selective barrier betwixt maternal and fetal cells, preventing maternal blood, proteins and microbes (including leaner and most viruses) from crossing the maternal-fetal barrier.[27] Deterioration in placental operation, referred to as placental insufficiency, may be related to mother-to-child transmission of some infectious diseases.[28] A very small number of viruses including rubella virus, Zika virus and cytomegalovirus (CMV) can travel across the placental barrier, generally taking advantage of conditions at sure gestational periods as the placenta develops. CMV and Zika travel from the maternal bloodstream via placental cells to the fetal bloodstream.[27] [29] [30] [31]

Beginning as early as thirteen weeks of gestation, and increasing linearly, with the largest transfer occurring in the third trimester, IgG antibodies can pass through the human placenta, providing protection to the fetus in utero.[32] [33] This passive amnesty lingers for several months after birth, providing the newborn with a carbon re-create of the mother's long-term humoral amnesty to run across the baby through the crucial kickoff months of extrauterine life. IgM antibodies, because of their larger size, cannot cantankerous the placenta,[34] 1 reason why infections acquired during pregnancy can be peculiarly chancy for the fetus.[35]

Endocrine function [edit]

- The first hormone released by the placenta is chosen the human chorionic gonadotropin hormone. This is responsible for stopping the process at the cease of catamenia when the Corpus luteum ceases activity and atrophies. If hCG did not interrupt this process, it would lead to spontaneous abortion of the fetus. The corpus luteum besides produces and releases progesterone and estrogen, and hCG stimulates information technology to increase the amount that it releases. hCG is the indicator of pregnancy that pregnancy tests look for. These tests will work when menses has non occurred or after implantation has happened on days seven to ten. hCG may besides have an anti-antibody effect, protecting it from being rejected by the female parent's body. hCG too assists the male person fetus past stimulating the testes to produce testosterone, which is the hormone needed to allow the sex organs of the male to grow.

- Progesterone helps the embryo implant past assisting passage through the fallopian tubes. Information technology also affects the fallopian tubes and the uterus by stimulating an increase in secretions necessary for fetal nutrition. Progesterone, like hCG, is necessary to prevent spontaneous abortion considering it prevents contractions of the uterus and is necessary for implantation.

- Estrogen is a crucial hormone in the procedure of proliferation. This involves the enlargement of the breasts and uterus, allowing for growth of the fetus and product of milk. Estrogen is besides responsible for increased blood supply towards the terminate of pregnancy through vasodilation. The levels of estrogen during pregnancy can increase so that they are xxx times what a non-meaning woman mid-cycles estrogen level would be.

- Human placental lactogen is a hormone used in pregnancy to develop fetal metabolism and full general growth and development. Human placental lactogen works with Growth hormone to stimulate Insulin-like growth factor product and regulating intermediary metabolism. In the fetus, hPL acts on lactogenic receptors to modulate embryonic development, metabolism and stimulate production of IGF, insulin, surfactant and adrenocortical hormones. hPL values increase with multiple pregnancies, intact tooth pregnancy, diabetes and Rh incompatibility. They are decreased with toxemia, choriocarcinoma, and Placental insufficiency.[36] [37]

Immunological barrier [edit]

The placenta and fetus may be regarded as a strange trunk within the mother and must exist protected from the normal immune response of the mother that would cause information technology to exist rejected. The placenta and fetus are thus treated as sites of immune privilege, with immune tolerance.

For this purpose, the placenta uses several mechanisms:

- Information technology secretes Neurokinin B-containing phosphocholine molecules. This is the same mechanism used by parasitic nematodes to avoid detection past the allowed system of their host.[38]

- There is presence of small-scale lymphocytic suppressor cells in the fetus that inhibit maternal cytotoxic T cells by inhibiting the response to interleukin 2.[39]

All the same, the Placental barrier is non the sole means to evade the immune arrangement, as strange fetal cells also persist in the maternal circulation, on the other side of the placental bulwark.[twoscore]

Other [edit]

The placenta also provides a reservoir of claret for the fetus, delivering blood to information technology in case of hypotension and vice versa, comparable to a capacitor.[41]

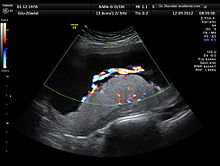

Ultrasound image of human placenta and umbilical cord (color Doppler rendering) with central cord insertion and 3 umbilical vessels, at twenty weeks of pregnancy

Clinical significance [edit]

Numerous pathologies tin affect the placenta.

- Placenta accreta, when the placenta implants besides deeply, all the way to the actual musculus of uterine wall (without penetrating information technology)

- Placenta praevia, when the placement of the placenta is also close to or blocks the cervix

- Placental abruption/abruptio placentae, premature disengagement of the placenta

- Placentitis, inflammation of the placenta, such as by TORCH infections.

Club and culture [edit]

The placenta oftentimes plays an important function in various cultures, with many societies conducting rituals regarding its disposal. In the Western world, the placenta is most often incinerated.[42]

Some cultures bury the placenta for various reasons. The Māori of New Zealand traditionally bury the placenta from a newborn child to emphasize the relationship between humans and the earth.[43] Also, the Navajo bury the placenta and umbilical cord at a specially chosen site,[44] peculiarly if the baby dies during nascency.[45] In Cambodia and Costa rica, burial of the placenta is believed to protect and ensure the health of the baby and the mother.[46] If a mother dies in childbirth, the Aymara of Bolivia coffin the placenta in a secret place then that the mother'southward spirit volition not return to claim her baby'due south life.[47]

The placenta is believed by some communities to have power over the lives of the baby or its parents. The Kwakiutl of British Columbia coffin girls' placentas to give the daughter skill in digging clams, and expose boys' placentas to ravens to encourage future prophetic visions. In Turkey, the proper disposal of the placenta and umbilical cord is believed to promote devoutness in the child after in life. In Transylvania, and Nippon, interaction with a disposed placenta is thought to influence the parents' future fertility.[ citation needed ]

Several cultures believe the placenta to be or have been alive, frequently a relative of the baby. Nepalese think of the placenta equally a friend of the baby; the orang Asli and Malay populations in Malay Peninsula regard it as the baby's older sibling.[46] [48] Native Hawaiians believe that the placenta is a part of the infant, and traditionally plant it with a tree that can and so grow aslope the kid.[42] Various cultures in Indonesia, such equally Javanese, believe that the placenta has a spirit and needs to be buried outside the family unit house. Some Malays would bury the infant's placenta with a pencil (if it is a boy) or a needle and thread (if it is a daughter).[48]

In some cultures, the placenta is eaten, a practise known equally placentophagy. In some eastern cultures, such every bit Cathay, the stale placenta (ziheche 紫河车, literally "purple river car") is idea to exist a healthful restorative and is sometimes used in preparations of traditional Chinese medicine and various health products.[49] The practice of human placentophagy has become a more recent trend in western cultures and is not without controversy; its practice existence considered cannibalism is debated.

Some cultures have alternative uses for placenta that include the manufacturing of cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and food.[50]

Boosted images [edit]

-

Fetus of nigh eight weeks, enclosed in the amnion. Magnified a fiddling over two diameters.

-

Placenta with attached fetal membranes, ruptured at the margin at the left in the image.

-

Micrograph of CMV placentitis.

-

A 3D Power doppler epitome of vasculature in xx-week placenta

-

Schematic view of the placenta

-

Maternal side of a whole human placenta, just later on birth

-

Fetal side of same placenta

-

Close-up of umbilical attachment to fetal side of freshly delivered placenta

-

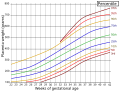

Placenta weight by gestational age[51]

-

Ziheche (紫河车), dried human placenta used in traditional Chinese medicine

Meet also [edit]

- Choriovitelline placenta

- Caul

- Zygote

- Pregnancy in fish

References [edit]

- ^ Pough, F. H.; Andrews, Robin Thou.; Cadle, John E.; Crump, Martha 50.; Savitsky, Alan H.; Wells, Kentwood D. (2004). Herpetology (third ed.). Pearson. ISBN978-0-xiii-100849-6. [ page needed ]

- ^ Mitra, Avir (31 January 2020). "How the placenta evolved from an aboriginal virus". WHYY . Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Chuong, Edward B. (nine October 2018). "The placenta goes viral: Retroviruses control cistron expression in pregnancy". PLOS Biological science. 16 (ten): e3000028. doi:ten.1371/journal.pbio.3000028. PMC6177113. PMID 30300353.

- ^ Villarreal, Luis P. (January 2016). "Viruses and the placenta: the essential virus get-go view". APMIS. 124 (1–ii): xx–30. doi:x.1111/apm.12485. PMID 26818259. S2CID 12042851.

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, "A Greek-English Lexicon", at Perseus Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Auto.

- ^ "placenta" Archived 2016-01-30 at the Wayback Motorcar. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Bowen, R. Implantation and Development of the Placenta: Introduction and Index. From: Pathophysiology of the Reproductive System. Accessed: 7 July 2019.

- ^ Test of the placenta Archived 2011-x-sixteen at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Placental Construction and Classification Archived 2016-02-xi at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fujikura, Toshio; Benson, Ralph C; Driscoll, Shirley G; et al. (1970), "The bipartite placenta and its clinical features", American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 107 (7): 1013–1017, doi:10.1016/0002-9378(70)90621-half dozen, PMID 5429965,

Bipartite placenta represented 4.2 per cent (366 of 8,505) of placentas of white women at the Boston Infirmary for Women who were enrolled in the Collaborative Project.

- ^ "The human proteome in placenta - The Human Poly peptide Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Archived from the original on 2017-09-26. Retrieved 2017-09-26 .

- ^ Uhlén, Mathias; Fagerberg, Linn; Hallström, Björn 1000.; Lindskog, Cecilia; Oksvold, Per; Mardinoglu, Adil; Sivertsson, Åsa; Kampf, Caroline; Sjöstedt, Evelina (2015-01-23). "Tissue-based map of the human being proteome". Science. 347 (6220): 1260419. doi:10.1126/science.1260419. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25613900. S2CID 802377.

- ^ Dashe, Jodi S.; Bloom, Steven L.; Spong, Catherine Y.; Hoffman, Barbara 50. (2018). Williams Obstetrics. McGraw Hill Professional person. ISBN978-1-259-64433-seven. [ folio needed ]

- ^ Placental claret circulation Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kiserud T, Acharya G (2004). "The fetal apportionment". Prenatal Diagnosis. 24 (thirteen): 1049–1059. doi:ten.1002/pd.1062. PMID 15614842. S2CID 25040285.

- ^ a b Reiter, R. J.; Tan, D. Ten.; Korkmaz, A.; Rosales-Corral, S. A. (2013). "Melatonin and stable circadian rhythms optimize maternal, placental and fetal physiology". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 293–307. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt054. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 24132226.

- ^ Williams book of obsteritcis.

- ^ Begley, CM; Gyte, GM; Devane, D; McGuire, W; Weeks, A; Biesty, LM (xiii February 2019). "Agile versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. two: CD007412. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007412.pub5. PMC6372362. PMID 30754073.

- ^ Mercer JS, Vohr BR, Erickson-Owens DA, Padbury JF, Oh W (2010). "Seven-month developmental outcomes of very depression birth weight infants enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of delayed versus immediate string clamping". Periodical of Perinatology. 30 (i): 11–half dozen. doi:10.1038/jp.2009.170. PMC2799542. PMID 19847185.

- ^ Perez-Muñoz, Maria Elisa; Arrieta, Marie-Claire; Ramer-Tait, Amanda Due east.; Walter, Jens (2017). "A disquisitional assessment of the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer babe icrobiome". Microbiome. 5 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4. ISSN 2049-2618. PMC5410102. PMID 28454555.

- ^ Mor, Gil; Kwon, Ja-Young (2015). "Trophoblast-microbiome interaction: a new paradigm on immune regulation". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (4): S131–S137. doi:x.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.039. ISSN 0002-9378. PMC6800181. PMID 26428492.

- ^ Prince, Amanda L.; Antony, Kathleen Thou.; Chu, Derrick Chiliad.; Aagaard, Kjersti M. (2014). "The microbiome, parturition, and timing of birth: more than questions than answers". Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 104–105: 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2014.03.006. ISSN 0165-0378. PMC4157949. PMID 24793619.

- ^ Hornef, One thousand; Penders, J (2017). "Does a prenatal bacterial microbiota exist?". Mucosal Immunology. 10 (3): 598–601. doi:x.1038/mi.2016.141. PMID 28120852.

- ^ Wright C, Sibley CP (2011). "Placental Transfer in Wellness and Disease". In Kay H, Nelson M, Yuping W (eds.). The Placenta: From Evolution to Illness . John Wiley and Sons. pp. 66. ISBN978-1-4443-3366-4.

- ^ Perazzolo Southward, Hirschmugl B, Wadsack C, Desoye K, Lewis RM, Sengers BG (February 2017). "The influence of placental metabolism on fatty acid transfer to the fetus". J. Lipid Res. 58 (two): 443–454. doi:10.1194/jlr.P072355. PMC5282960. PMID 27913585.

- ^ Kappen C, Kruger C, MacGowan J, Salbaum JM (2012). "Maternal diet modulates placenta growth and gene expression in a mouse model of diabetic pregnancy". PLOS I. seven (6): e38445. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738445K. doi:10.1371/periodical.pone.0038445. PMC3372526. PMID 22701643.

- ^ a b Madhusoodanan, Jyoti (October ten, 2018). "Suspension on through: How some viruses infect the placenta". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-101018-1.

- ^ Erlebacher, Adrian (2013-03-21). "Immunology of the Maternal-Fetal Interface". Annual Review of Immunology. 31 (one): 387–411. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-100003. PMID 23298207. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Pereira, Lenore (2018-09-29). "Congenital Viral Infection: Traversing the Uterine-Placental Interface". Annual Review of Virology. v (one): 273–299. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-092917-043236. PMID 30048217. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ Arora, Nitin; Sadovsky, Yoel; Dermody, Terence South.; Coyne, Carolyn B. (May 2017). "Microbial Vertical Transmission during Human Pregnancy". Cell Host & Microbe. 21 (5): 561–567. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2017.04.007. PMC6148370. PMID 28494237.

- ^ Robbins, Jennifer R; Bakardjiev, Anna I (February 2012). "Pathogens and the placental fortress". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 15 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2011.xi.006. PMC3265690. PMID 22169833.

- ^ Palmeira, Patricia; Quinello, Camila; Silveira-Lessa, Ana Lúcia; Zago, Cláudia Augusta; Carneiro-Sampaio, Magda (2012). "IgG Placental Transfer in Good for you and Pathological Pregnancies". Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2012: 985646. doi:10.1155/2012/985646. PMC3251916. PMID 22235228.

- ^ Simister Northward. Due east., Story C. M. (1997). "Human placental Fc receptors and the manual of antibodies from female parent to fetus". Periodical of Reproductive Immunology. 37 (1): ane–23. doi:10.1016/s0165-0378(97)00068-5. PMID 9501287.

- ^ Pillitteri, Adele (2009). Maternal and Child Health Nursing: Intendance of the Childbearing and Childrearing Family. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 202. ISBN978-i-58255-999-5.

- ^ "What infections can touch pregnancy?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development . Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ Handwerger Due south, Freemark Grand (2000). "The roles of placental growth hormone and placental lactogen in the regulation of human fetal growth and development". Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology & Metabolism. 13 (iv): 343–56. doi:ten.1515/jpem.2000.thirteen.4.343. PMID 10776988. S2CID 28778529.

- ^ "Human Placental Lactogen". world wide web.ucsfhealth.org. May 17, 2009. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2017.

- ^ "Placenta 'fools body's defences'". BBC News. ten Nov 2007. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012.

- ^ Clark DA, Chaput A, Tutton D (March 1986). "Active suppression of host-vs-graft reaction in pregnant mice. Vii. Spontaneous abortion of allogeneic CBA/J x DBA/2 fetuses in the uterus of CBA/J mice correlates with deficient non-T suppressor prison cell activeness". J. Immunol. 136 (5): 1668–75. PMID 2936806.

- ^ Williams Z, Zepf D, Longtine J, Anchan R, Broadman B, Missmer SA, Hornstein MD (March 2008). "Foreign fetal cells persist in the maternal circulation". Fertil. Steril. 91 (six): 2593–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.008. PMID 18384774.

- ^ Assad RS, Lee FY, Hanley FL (2001). "Placental compliance during fetal extracorporeal circulation". Journal of Applied Physiology. ninety (v): 1882–1886. doi:10.1152/jappl.2001.xc.v.1882. PMID 11299282.

- ^ a b "Why swallow a placenta?". BBC News. 18 April 2006.

- ^ Metge, Joan (2005). "Working In/Playing With 3 Languages". Sites: A Periodical of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies. ii (two): 83–90. doi:10.11157/sites-vol2iss2id65.

- ^ Francisco, Edna (3 December 2004). "Bridging the Cultural Divide in Medicine". Scientific discipline.

- ^ Shepardson, Mary (1978). "Changes in Navajo mortuary practices and beliefs". American Indian Quarterly. 4 (4): 383–96. doi:ten.2307/1184564. JSTOR 1184564. PMID 11614175.

- ^ a b Buckley, Sarah J. "Placenta Rituals and Folklore from effectually the World". Mothering. Archived from the original on 6 January 2008. Retrieved vii January 2008.

- ^ Davenport, Ann (June 2005). "The Love Offer". Johns Hopkins Magazine. 57 (3).

- ^ a b Anisah Barakbah (2017). Ensiklopedia Perbidanan Melayu. Universiti Islam Malaysia Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN978-967-13305-9-3.

- ^ Falcao, Ronnie. "Medicinal Uses of the Placenta". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 25 Nov 2008.

- ^ Kroløkke, Charlotte; Dickinson, Elizabeth; Foss, Karen A (May 2018). "The placenta economy: From trashed to treasured bio-products". European Journal of Women'due south Studies. 25 (2): 138–153. doi:10.1177/1350506816679004. ISSN 1350-5068.

- ^ "Placental Weights: Means, Standard Deviations, and Percentiles past Gestational Historic period". Placental and Gestational Pathology. 2017. p. 336. doi:10.1017/9781316848616.039. ISBN978-1-316-84861-6.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Placenta. |

| | Expect up placenta in Wiktionary, the gratuitous lexicon. |

- The placenta-specific proteome at the Human being Poly peptide Atlas

- The Placenta, gynob.com, with quotes from Williams Obstetrics, 18th Edition, F. Gary Cunningham, M.D., Paul C. MacDonald, M.D., Norman F. Grant, M.D., Appleton & Lange, Publishers.

mckinneytagning1948.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Placenta

0 Response to "Ultrasound Reading of Fluid Between Baby and Placenta More Than 3.5 Cm"

Post a Comment